Following legal industry workshops and interviews across Australia, New Zealand and the UK, Unispace Global Design Director Simon Pole presents the first in a series of blogs focused on recalibrating how we think about the legal workplace.

In recent years, the legal industry has found itself swept up in a wave of disruption. With drivers of change ranging from AI to big data, virtual assistants to outsourcing, law firms are also dealing with an increased need to support cross disciplinary teams and the diverse needs of four generations of workers.

To understand these issues further, throughout 2016 Unispace ran a series of workshops and interviews with some of the most notable top and mid-tier law firms in the UK, Australia and New Zealand. We also spoke to lawyers and ex-Partners who had moved on to become in-house counsel at leading pharmaceutical, construction and technology organisations.

The results between countries were polarising to say the least.

When the idea of ‘culture’ was mentioned during our workshops in Australia and the UK, there was a sharp intake of breath and commentary along the lines of “what culture?” It was revealed that, deeply set amongst the industry, a ‘churn and burn’ mentality exists, accompanied by a boy’s club “up or out” unwritten rule.

We all know that lawyers traditionally work extremely long hours but what was never clear to me, is why the practice of law is so exclusive, prestigious and well paid. Over the years, I’ve heard anecdotes of junior lawyers being the last one out the door at the end of a long day because they sought validation by being at the Partner’s beck and call. But, when we began to uncover the other side of the story, I realised how law firms keep internal competition high, with a view to breeding a mentality aligned with the unwritten rules.

Interestingly, during our New Zealand sessions, attraction and retention of locally-educated professionals was revealed as a major focus. New Zealand is the third in the world, behind the US and Brazil, when it comes to lawyers per capita, with one lawyer per 391 citizens[i]. Ambitious lawyers that don’t have a perceived route to partnership, or are seeking broader practice experience within a global firm, tend to look for career opportunities overseas in larger markets such as Australia and the UK. Therefore, firms position themselves to ensure that if an employee returns to New Zealand, they would look favourably upon their previous experience from a cultural perspective, which in turn could be leveraged, utilising their international experience and secure local clients.

Although talent retention was not a major priority to those we spoke to in hot markets such as the UK, attraction most certainly was. Investment in prestigious locations and premium quality buildings was high on the agenda, as it helps elevate the firm’s brand and attract better clients, which in turn lures talent.

To further support attraction and retention, law firms are increasingly supporting the need for work/life balance. For example, Australian statistics show that as at January 2017, up to 24% of Partners were working either part time or choosing to work flexible hours[ii]. This is a marked improvement on the traditional hours a lawyer is usually trapped in their office.

Another recurring theme in our discussions was the impact of the traditional route to partnership for professional women. In the past, conversations I’ve had describing the boy’s club are slowly eroding. In fact, a recent article demonstrates a small but steady increase in gender balance, with women now making up nearly 25% of all partners at Australian law firms[iii]. In larger firms, we’re seeing an increase in parenting and family rooms, but still haven’t seen the same strong emphasis around family when compared to other industries such as banking and professional services.

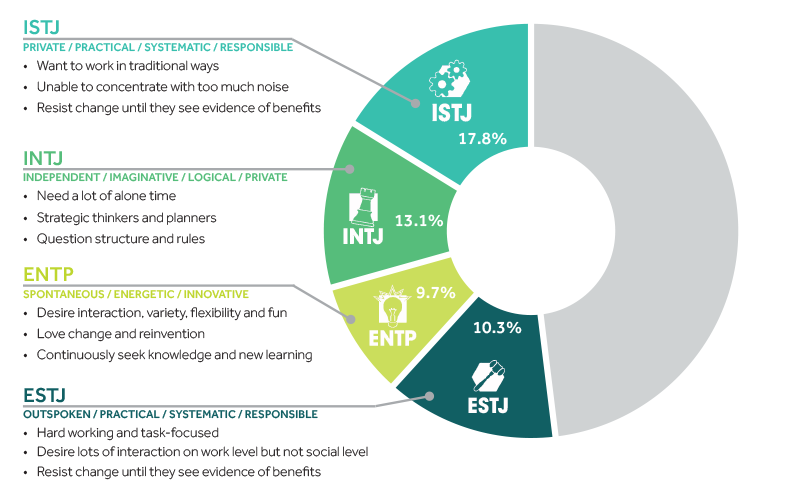

To understand in more depth what draws an individual to law, we began to analyse the unique personality traits of a lawyer. We discovered that research conducted by Dr Larry Richard, using the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator (MBTI), reflects some fascinating insights into those most ideally suited to the practice of law[iv]. In stark contrast to general population statistics, of the 16 MBTI types, more than 50 percent of practicing lawyers fall into one of four groups: ISTJ, INTJ, ENTP and ESTJ.

What makes this even more interesting is that the INTJ personality type occurs with five times greater frequency in lawyers than it does the general population. INTJs are also the only one of the 16 MBTI types for whom an elevated IQ has been statistically correlated. For me as a workplace designer, it’s difficult to understand how we got to a position where a one-size-fits-all solution is the desired norm for most firms and why we revert to looking at benchmarks within the legal industry and constantly fall into the same traps.

All too often, the physical workplace is created for a utopian vision of ‘set and forget’ architecture, where everyone is created equal and multiple work personas are expected to succeed in a cookie cutter environment.

We need to get back to understanding, in a more scientific way, what people working within the legal industry need to do their job as productively as possible. Whether it’s an enclosed office or a beanbag, we know from our global research that Partners use their offices the least and Associates not only spend over 70% of their time on focused work, but are the highest users of the workplace environment on average. So why not give them the corner office?

[i] http://www.nzherald.co.nz/nz/news/article.cfm?c_id=1&objectid=10659064

[ii] http://www.afr.com/business/legal/law-firms-embrace-flexible-working-20170203-gu4rsa

[iii] http://www.afr.com/business/legal/one-in-three-new-legal-partners-are-women-20160629-gpulic

[iv] http://abovethelaw.com/2014/05/deviations-from-the-norm-the-lawyer-type-and-legal-hiring/